If you try and explain precision approaches in sentence form you can write for days. The nuances of ILS approaches or approach plates can fog the brain with minutia. My problem with these complex subjects is that the books or articles you read rarely just summarize the important data to help simplify the review of the subject.

The following is a fact summary I have compiled from many different sources. The limitation to this summary for others is that I have only VOR approach capability. I do not have an IFR GPS or even a DME unit. Therefore, specific issues related to these approaches will not be contained in this list.

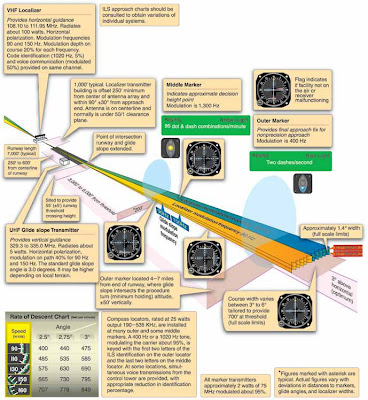

The Five Parts of a Localizer Approach

Localizer

Glide slope

Threshold crossing height

Outer marker

Middle marker

LOM: Locator Outer Marker - approx. 5 miles from the runway

Localizer

Glide slope

Threshold crossing height

Outer marker

Middle marker

LOM: Locator Outer Marker - approx. 5 miles from the runway

LMM: Locator Middle Marker - approx. 1/2 mile from threshold and at about where the glideslope intersects decision height.

Localizer identifier always begins with "I" (dot dot) and frequencies are always on "odd tenths" - e.g. 108.1, 108.15, 108.3, 108.35

Localizer signal is 700 feet wide at threshold

If Nav receiver has 5 dots then each dot equals 300 feet at the outer marker

Needle readings may be unreliable more than 35 degrees from the course

Localizer is aligned within 3 degrees of runway centerline

Glideslope:

If followed to touchdown an aircraft would touch down on the fixed distance marker 1000 feet from the threshold

- the GS signal is not usable all the way to touch down. It becomes

unusable 18 to 27 feet above the ground

- signal is typically transmitted at a 3 degree angle

- at the outer marker the signal is approx 50 feet per dot

- it is common sense to fly at or above the glideslope as not much terrain clearance is provided

- on a bumpy day consider flying one dot high

- the MAP on a precision approach is called Decision Altitude (DA)

- on the marker beacon a " high" setting means reception over a greater area and less precise position identification. Normally set to low position. Turn up volume.

- the outer and middle marker beacons provide range information but neither is required for the approach. The outer marker is located at the approx. point where the glideslope intersects the intermediate approach altitude however it should not he treated as the final approach fix. Descent begins at the glideslope intercept point.

Glideslope:

If followed to touchdown an aircraft would touch down on the fixed distance marker 1000 feet from the threshold

- the GS signal is not usable all the way to touch down. It becomes

unusable 18 to 27 feet above the ground

- signal is typically transmitted at a 3 degree angle

- at the outer marker the signal is approx 50 feet per dot

- it is common sense to fly at or above the glideslope as not much terrain clearance is provided

- on a bumpy day consider flying one dot high

- the MAP on a precision approach is called Decision Altitude (DA)

- on the marker beacon a " high" setting means reception over a greater area and less precise position identification. Normally set to low position. Turn up volume.

- the outer and middle marker beacons provide range information but neither is required for the approach. The outer marker is located at the approx. point where the glideslope intersects the intermediate approach altitude however it should not he treated as the final approach fix. Descent begins at the glideslope intercept point.

- the outer marker flashes blue and emits dots at 120 dashes per minute. It intercepts the glideslope at the intermediate approach altitude – however it is not the final approach fix.

- the middle marker flashes amber and emits dots AND dashes at 95 of each per minute. It is located approximately where the decision altitude is reached, although it is not used to identify the missed approach point.

- The inner marker flashes white at a rate of 360 dots per minute and is located near the runway threshold

- when decision altitude is reached there is no leveling off. Either you see the runway environment or you immediately begin the missed approach.

- You can help verify the glideslope signal by comparing the crossing altitude at the outer marker with the altitude shown on the approach plate. A discrepancy means either a false glideslope signal, a malfunctioning glideslope receiver or the altimeter is incorrectly set.

- The HAT, or Height Above Touchdown, are shown in small numbers after the MDA’s and DH’s in the minimum sections of the approach plate ie: 222/24 200. In this case the TDZE (touch down zone elevation) is 22 feet so the HAT is 200 feet.

- TCH – threshold crossing height: The height above the runway where the glideslope intersects.

There are three categories of precision approaches:

Category 1: provides height above touchdown of not less than 200 feet

Category 2: provides height above touchdown of not less than 100 feet